Right now, I seem to be the guy that is forever speaking about user contexts and in particular, talking about the nature of how people behave in different environments and their resulting use of technology within those environments. My talk at Web Directions 2012 focussed on this with respect to use of web tech, but this has also been a primary part of the research that I set up Rocket Melbourne to look into.

What has mostly inspired this essay is that it seems like every week a new piece of ambient technology is being launched on kickstarter - often to almost Apple-like levels of hype (OMG this is totally going to change the tweet notification market forever). I'm not going to talk about any one of these products specifically because I wish them all the best and more people doing hardware is a great thing.

Rather, I want to document some of my own findings, some insight from observing (and purchasing) a lot of ambient technology products, and hopefully highlight areas where people should be working in this space.

What is ambient tech?

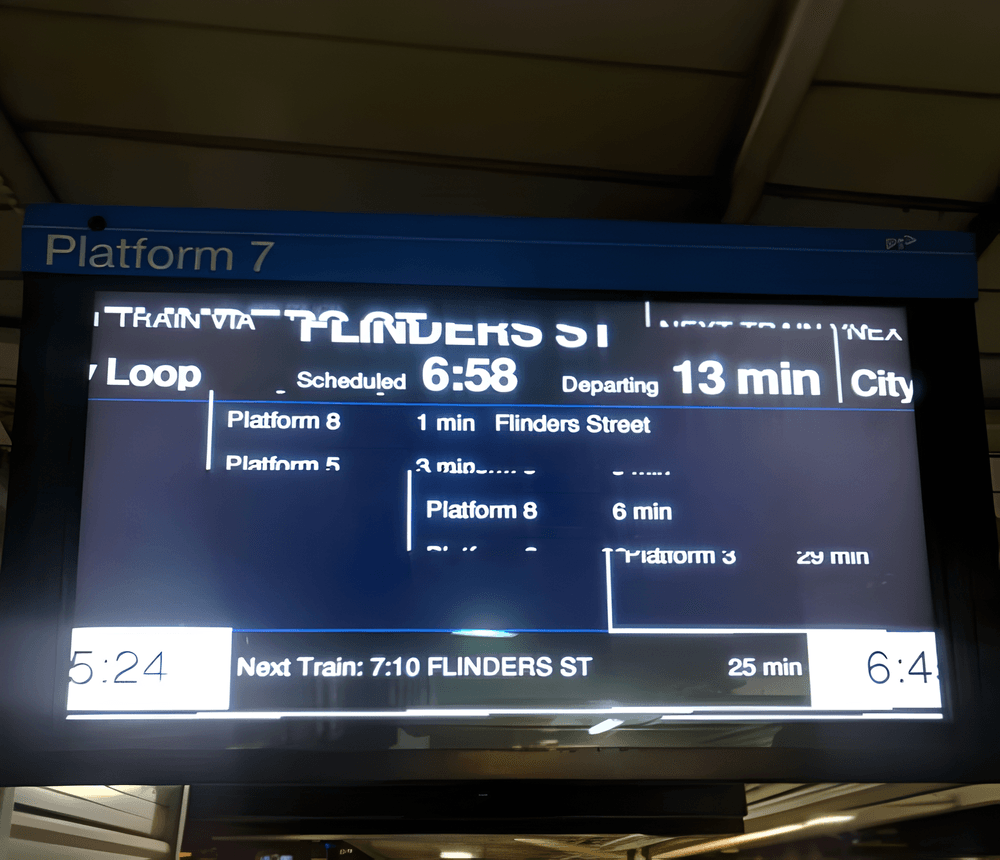

As you read this, you probably have many pieces of digital ambient display or technology around you. If you're on a PC, chances are there's a clock in one of the corners of your screen. If you're on a mobile device when you go back to your home screen you may have widgets (if you're on Android) or badges (if you use iOS) showing how many emails or tweets you have unread. You may be reading this while standing on a train station platform where there will be signage indicating how long until the next train arrives.

Or, if you live in a house like mine you'll have many gadgets, all sporting lights that are blinking on and off various colours to indicate a stack of different things that are going on around you; from numbers of people hitting my blog, to chirping when I get @ed on twitter to hot / cold indicators showing me my inbox level.

And that's before we get to expert user systems such as the dashboard on your car, which provides an inordinate amount of information to the driver at a glance, and is being augmented further via smart heads up display (HUD) technology projected onto the windscreen.

Ambient technology can encompass all these things and a lot more besides. In essence, it's a method of presenting information to consumers that is "around you". It's not typically "sit down at a computer and get it" type information - typically it's embedded into our environment, hence the ambient part of it.

In many cases there is some form of socially-created encoding involved, such as the signs for the availability of a bathroom on an aeroplane that switch from red to green showing busy or vacant. With many pieces of ambient technology you have to be told what it's doing or else build upon your knowledge of similar icons in order to bootstrap that knowledge. The bathroom light builds on our cultural knowledge of stop / go colours as well as socialisation that teaches us about the states of bathrooms.

Good ambient technology is also actionable - it provides you with information allowing you to make a decision based on the data encoded within it - should you choose to act on it. To continue the bathroom light example; you can decide whether it's worth getting up out of your chair based on the bathroom state, or consider going to one end of the cabin rather than the other. This provides efficiency in movement, allowing aisles to be kept clear, and crew to move around easily.

It's worth noting also that ambient display information is "nice to have" and not critical. It is different from, say, a warning sign or an alarm, which requires attention and action to be taken. With the bathroom example, if you ignore the light, you can still head to the bathroom, you'll just need to wait when you get there.

The bathroom status light is a simple example but one that is familiar and creates an actionable outcome from very simply encoded data. Thankfully, this will be the last time I talk about bathrooms on aeroplanes in this essay.

Ambient display

Ambient display is a very specific form of ambient technology. This is usually referring to showing information in a visual mode - whether through the use of light or more traditional display methods (screens, matrix boards etc). It's fairly common, as we can produce displays very easily, however all the senses can be engaged in ambient technology with the right design.

What's all this got to do with context?

Context is really important to how people use and interact with technology and services. Anyone that spends a lot of time jumping between different computing devices will know all about context and context failures.

Try to reply to a message of some sort on your phone while you walk down a crowded street (DO NOT try this if you're driving).

Observe the information you pay attention to when you're navigating somewhere in a public space you don't know. What signs do you look at? When do you look at a map? Can you hold a conversation and navigate at the same time?

How do you perform when you have to process difficult information late in the afternoon versus in the morning?

All of these things are different aspects of context and it is something that is constantly changing around us. There are many variables that shape our context as well. I often talk about location, time, connection speed and device capabilities for web tech, however context is driven by an almost infinite number of variables. When we consider humans in an environment, we consider cultural norms, symbolic education, proficiency with the service being used, mental state, noise, distractions and all sorts of other things that affect our behaviour.

Any time we talk about humans and technology or services, context should be one of the immediate things we consider.

What I want to try and do with this essay is to consider the ways ambient technology can be deployed and consider the contexts that work best for different types of ambient information.

A contextual model for ambient technology

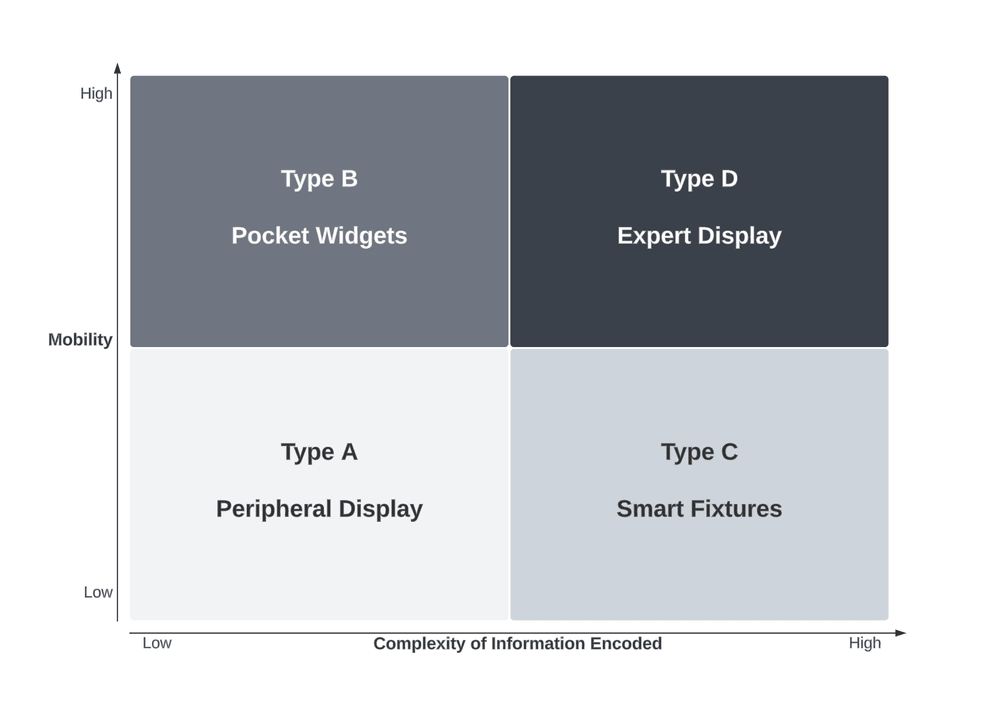

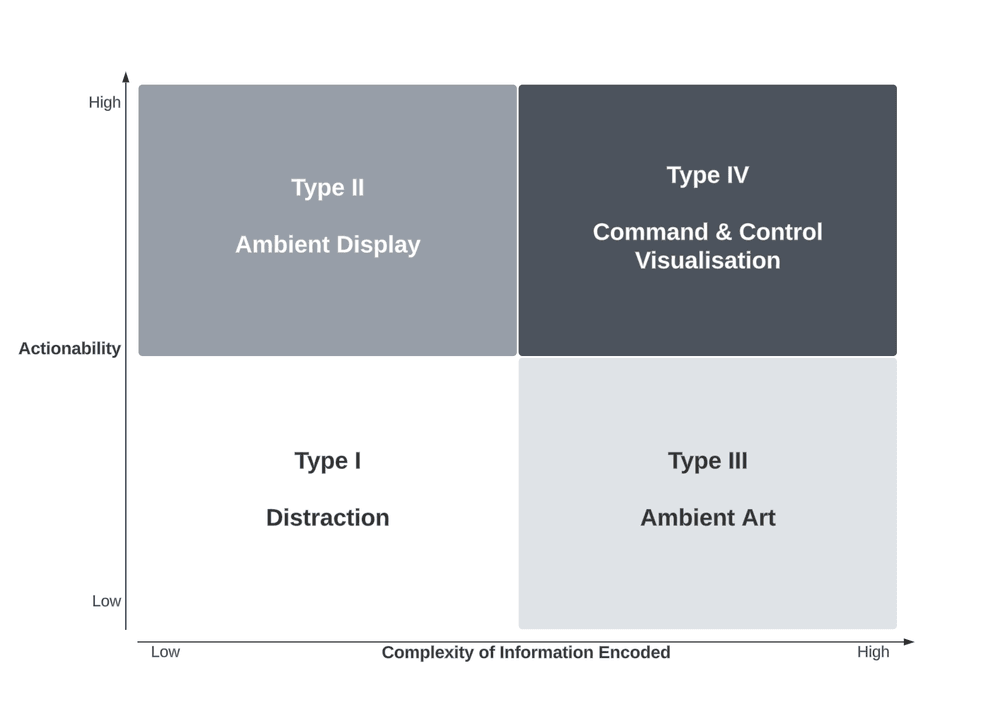

The model I've built uses two, four-quadrant comparison charts comparing three variables.

In the first part of the model, I consider the complexity of the information being displayed against how mobile the display is within the environment. Mobility of information is becoming more important to humans, primarily as a result of always-connected smartphones which can allow themselves to operate as a generic ambient display endpoint. This can be seen in the four-quadrant chart below.

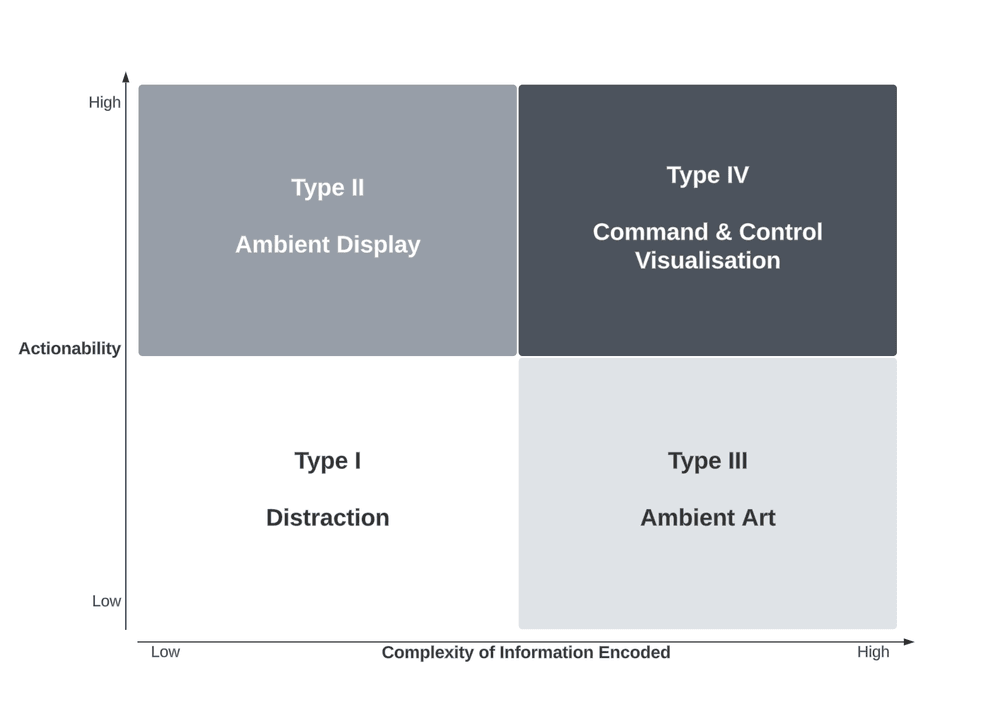

The second part of the model compares the variables of actionability against the complexity of information instead. As we have seen from advances in Data Science, taking large amounts of data and distilling it down is important, but being able to trigger actions as a result of that information is even more important and useful. This can be seen in the chart below.

Complexity of information is presented as the X-axis in both parts of the model so will be discussed here. This represents how much information is encoded and is being presented to the user. It is worth noting that the same piece of information can be encoded in different ways and represent different levels of complexity. Complexity comes down to how tolerant of precision we are in different situations and the ambiguity inherent in the choice of information encoding.

For example take a counter of some event such as unread messages in an inbox. A board with the number shown has very low complexity. If we encoded that same data on a scale from blue being zero to red being one hundred on a linear range between, then this becomes more complex to understand without reducing precision. Instead, the encoded data must be reduced in complexity to “a lot” or “not many” rather than 78 or 3.

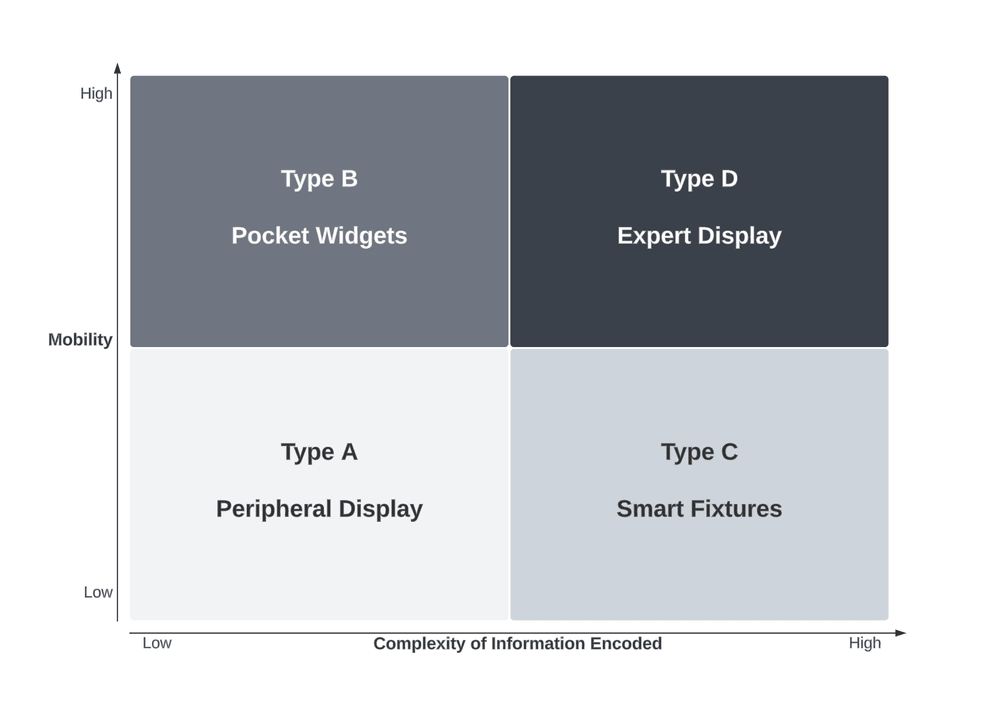

The following sections explore the model in more detail and illustrate the types of ambient technology that work well within each of the quadrants when taking the mobility or actionability variables into account.

Complexity of information versus mobility of display

In the first part of the model, along with complexity, we consider mobility of the display as our other variable and is represented on the Y axis. The chart is repeated again here so you don't need to scroll back up.

Mobility in this case, represents how fixed the technology is to a specific location. A mobile phone is obviously a highly mobile piece of ambient technology however the flight status board fixed to a wall at an airport is stationary so has very low mobility.

There are some inherent assumptions that go along with mobility, namely that the technology is able to be powered and probably has some type of connection to data via a network or other means (e.g. displaying direct sensor data from its local environment).

The four types of of mobile ambient technology, with examples are highlighted in the following sections.

Type A: Peripheral display (Complexity:L / Mobility:L)

Peripheral display is probably the most common type of ambient technology currently deployed. This is the most common starting point for anyone new to Internet of Things related ambient technology. In this category are mostly lights that illuminate based on some arbitrary action (eg pulsing based on tweets with a certain hashtag).

This type of display can run the risk of being a distraction because it often encodes information that may be peripherally available anyway. The very common email notification light is an example of this - most people have the status of their email in their pocket courtesy of their smartphone. As a result, the information is too simple to be useful and redundant due to other means of conveying it (thus leading to it becoming low value to the user).

Where this type of ambient technology works best is when the encoded information is not in the information space of the environment already (that is, it is not redundant) as shown in the following examples.

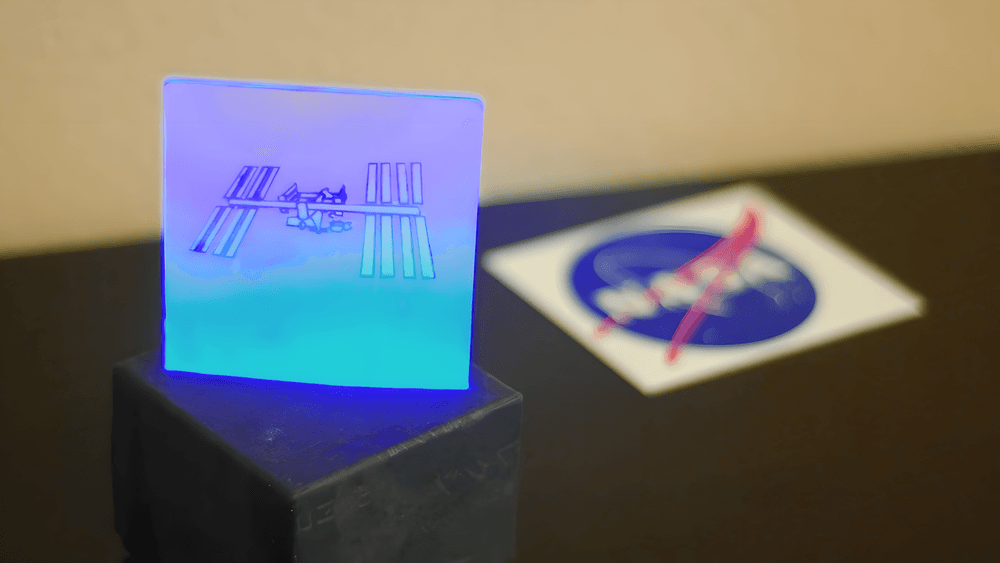

ISS Notify

This lamp lights up every time the International Space Station passes over the location where the lamp is employed. The idea was originally simply as a visualisation that the ISS was passing overhead and to highlight that there are humans permanently in space. NASA endorsed the project and the kickstarter was well backed and supported. The value of this visualisation comes from the data not being readily present in our environment especially as the ISS passes overhead often through the day where it cannot be seen.

Smart lighting

Becoming common in car parks, smart lighting is helping to solve the problems of "where can I park my car". This system relies on a pressure sensor in the floor (or ultrasonic range sensor to see if a car is below it) and a simple bright LED above each car park which displays red if a car is parked in the spot or green if it is available. Additional information can be encoded such as blue for disabled car parks etc. Arguably, the value of this information is relatively low, however given its increasing popularity in car parks around the world there must be at least a perception of increased traffic flow within the car park compared to the costs of fixture (which are now extremely low).

Type B: Pocket Widgets

(Complexity:L / Mobility:H)

Low complexity, high mobility ambient devices are, at this time, heavily skewed towards indicators that are present in our mobile devices in passive mode. This distinction is that the mobile phone (or tablet) is in a restful state - i.e. without the operator taking complex actions to get at information. This is the information provided in the lock state of the device or in its standard “home screen” mode.

Smartphones are clearly capable of much higher function, however, for the vast majority of the time, their use is in a low function passive mode, only one step up from true standby. Regardless of their passive modality, the devices are still permanently connected to the network and arguably it was the smartphone which truly realised the way "always on, always connected" would pervade our day to day rather than permanently connected Internet at home or work.

Due to high levels of mobility whilst (mostly) maintaining network connectivity, a passive mode smartphone can provide a large array of ambient information that is very easy to understand with simply a glance at the device or via auditory means as well via connected headphones (or speaker).

This type of technology works best where there is a need to have information of very low complexity available at any point in an environment that a consumer may find themselves. This is why smartphone widgets and notifications are currently driving this area of ambient tech.

However, this class of device can also encompass other, highly mobile but low complexity means of displaying information such as bespoke, hand held sensor devices. An example would be a radiation dosimeter which shows the amount of radiation a person has been exposed to and is highly contextual to the individual using it and the location that they find themselves in but only shows a very simple piece of information.

Weather widget (Android)

A simple glance at the screen provides current weather as well as a forecast for five days ahead. Utilising well known cultural symbols, the weather widget is a fixture on the home screens of most Android user's devices. Utilising the sensors in the phone to understand location (GPS or coarse grained location data) allows this data to be constantly updating no matter where the user is in the world (so long as they have a working network connection to update from).

Type C: Smart fixtures

(Complexity:H / Mobility:L)

When you combine high complexity of information with low mobility you move into the realms of Smart Fixtures. These are devices that are fixed in their environment - digital signage is an obvious example - but are afforded great capability as a result. Being built into the environment generally results in better power supply (eg mains power) and connectivity (eg wired rather than wireless network). Reliable power, network and a largely fixed environment affords greater options for display and processor speeds as well.

Many of these devices tend to run on a more traditional PC-based architecture rather than embedded systems as we see in other categories. In many cases, due to the commodity nature of this hardware, the devices are drastically over specified too. The side effect of this is that they are more capable of being enhanced in place with additional capability over time and can also do on-site data processing - something that is extremely difficult in memory constrained embedded systems.

The best environments for these types of systems are those where there is a large volume of information that needs to be displayed or where there is a large amount of change in the data being displayed. Smart fixtures are also valuable where the data to be displayed requires a degree of precision to convey useful information.

Adaptive wayfinding

Increasingly common in airports as well as shopping centres and conference locations, adaptive wayfinding provides a means for signage to adapt to external information. The classic example is the departure and arrivals board at an airport or large train station. With the increasing prevalence of digital signage in public spaces this will get more sophisticated and may eventually be able to adapt to the individual standing in front of it.

Imagine for example, an RFID or NFC encoded boarding pass which updates the displays in an airport as you walk near them in order to direct you to your departure gate. No more mad dashing around unfamiliar spaces looking for that transfer desk and subsequent flight you're almost late for.

Fixed visualisations

More and more buildings are starting to incorporate digital displays as part of the material from which they are built. Whilst some are practical, such as the ubiquitous stock price ticker you see in many financial locations, others can be more artistic or abstract in nature.

As this class of smart fixtures start to straddle traditional architecture, the information that is visualised and the way it is presented (explicitly or more abstract) helps contribute towards the overall feel of the environment and its subsequent use.

The team at the Rockwell Group lab are particularly adept at this as they are constantly looking at ways to merge digital and architectural experiences.

Plug-In-Play from labatrockwell on Vimeo.

This example from a project they worked on called Plug in Play in San Jose uses projection along with data fed in from a variety of social and internal sources (eg tweets nearby or car traffic density) to help show all the data that is being created within the community. This starts to draw a story about community and citizenship and how people interact with the civic space it was designed for.

One of my favourite versions of this was a project done out of Sydney University that was extremely low tech so is not quite a "smart fixture" but shows the potential for smart fixtures in our environment in the future. The Neighbourhood Scorecards project highlighted energy usage on a series of black boards attached to the front of some homes in Sydney.

The information was real though the means of updating was very manual. These visualisations encode very complex information in an ambient manner where they could be used to affect behaviour (those homes that had the displays decreased their energy usage the most compared to controls who did not).

Little printer

This is probably one of the first Internet of Things devices that plays directly into the Smart Fixtures category of ambient technology. Conceptually this product makes a move beyond the "twitter light" style interactions prevalent in Type A ambient technologies and forces a higher level of precision of the content that is produced on the printer.

Hello Little Printer, from Berg on Vimeo.

The device itself is a little thermal printer designed in a quirky body - not dissimilar to a receipt printer on a cash register - that connects to the network and can print content supplied to it via Berg's "Berg Cloud". Thus, the printer will deliver pieces of content such as what are good things to cook, a summary of your calendar for the day or a weather forecast (as well as a lot more by subscribing to channels) whenever it is appropriate to do so.

Arguably the true success of this product will be how many people replace the printer roll and continue to consume the information. The interesting aspect to this is how the device is being used to bring pieces of ambient information into the physical world and bridge the digital back into a very tangible, physical experience - after all you're delivered a piece of paper with real information on it. Moreover it transcends the mobility issues by allowing a piece of content to be removed from the physical installation and taken with you (such as your diary snapshot) whilst the physical device remains in situ.

Type D: Expert display

(Complexity:H / Mobility:H)

To have complex information available and have it highly mobile at the same time as it being ambient in nature implies that it is probably Augmented Reality or an extremely specialised mobile system (such as those used in hospitals for patient monitoring).

What I find interesting with this space is that it highlights the failings of a lot of AR that has been made to date and I think also highlights some of the contextual flaws that things like Google Glass may develop if left unchecked.

From an AR perspective, this is really about heads up displays (HUDs) for experts. What I mean by this is that the data is very complex and highly environment specific. The types of applications where this type of ambient technology will be most useful will be in military (and probably industrial) contexts where additional complex information is overlaid with the real world in order to support better decision making power.

It is easy to imagine the military applications of this once it is reliably mobile, lightweight and network connected. This type of display has historically only been present in the visors of pilots who are strapped into an aircraft equipped with sensors and jacked into a field from their command and control systems.

Arvika was exploring the use of data layered into their vision to help mechanics when they are working on machinery (for example providing the tolerances for components).

I can envisage similar scenarios where field engineers are provided with information by data science teams overlaid onto sites they are working on to help them make better on-the-ground decisions.

Similarly, imagine surgery conducted where the surgeon could have a patient's vitals in their peripheral field of vision rather than on a machine that is cluttering the operating theatre. Taken further, a similar system could overlay imaging information over a patient, giving the practitioner a first person view of what is going on within the patient they are treating.

Unfortunately, this type of ambient technology is drastically less glamorous than the Iron Man Mark VII HUD or Google Glass showing you what your friends have just +1'ed. I think the killer use cases for this type of ambient display will remain in industrial applications for the foreseeable future before someone finds an appropriate consumer-oriented use case for it.

Complexity of information versus actionability of data

In the second part of the model we consider the actionability of information on the Y axis. Again, the chart is repeated so you don't need to scroll back up.

Actionability in this case is an indicator of how well the person interpreting the information can take action upon it if they choose to. For example an SMS notification on a mobile phone is a highly actionable piece of data (you can instant reply or open a dialogue to reply more fully with a single tap) but a tube of water visualising my current inbox level has low actionability as the data it encodes is distant from the means I use to action it (I can't read and reply to my email via a tube of water).

It's worth considering a definition of "actionability" for a moment because it's a fuzzy concept. When I'm talking about actionability I'm considering the ability of a human viewer of the system to take an action based on the information conveyed, that is in direct response to the data presented. There are two parts to this; the actionability as perceived by the user of the system, and the actionability as perceived by the designer of the system. Sometimes these can come into conflict; primarily because the designer hasn't expressed the right context for their device - whether implicitly in their design or explicitly by highlighting a use case.

In this case when I'm talking about actionability I am suggesting the “desired” action that can be taken either by the device itself or easily within the environmental locale of the device. An example may be a display on your wall telling you how many emails you have unread. By itself, this device has low actionability - there's not much you can do with that piece of data. Presented with a computer nearby or your smartphone to hand, however, and this device has high actionability as it can be used to prompt you to check your email and do something about it. Moreover, this same device can transition between low and high actionability by considering the designer's intent and the way the user ultimately uses it.

Actionability makes no judgement on the complexity of the action that results but it does assume some degree of action taken by the user.

Type I: Distractions

(Complexity:L / Actionability:L)

Much of the ambient technology I see falls into this quadrant and this is primarily due to the designer not having adequately considered the actionability of the information conferred on the observer. To move out of this quadrant, a designer needs to ask one fundamental question "What does the user DO with the information I am giving them?"

An acceptable answer may be "Nothing - it's just pretty" - at which case the device moves out of this quadrant and becomes a Type III device. Often, as expressed in the introduction to this part of the model, the desired action of the designer and of the user are two different things and this causes Type II devices to become Type I devices and become an unwanted distraction.

In my experiments in this area I've been responsible for building many Type I devices, so rather than criticising anyone else's work, I'll discuss my own as anti-patterns.

Twitter notification light

I built a lot of these sorts of things when I first started playing with networked arduinos. They allow computation to occur in one location (eg a server) but display can be had in another. Similar examples which I won't go into include email notification lights or some other notification that an event has occurred which is untethered from a computer.

Being untethered from a computer is important. In my research, this is what tends to drive actionability down. In theory, having a light that displays when you get mentioned in a tweet and illuminates without needing a computer sounds useful. In practice it is not, it's a distraction at best and useless at worst.

This was probably more useful several years ago, but in the age of smartphones that are typically less than a metre away from their owner at any point, they are rendered useless.

Location matters too, if the light is in my living room but I am in my bedroom, the device's utility has entirely disappeared as a result of it not being visible to me (thus no longer ambient). This goes back to the issue of mobility discussed in the earlier sections. The worst possible combination for ambient display is low complexity, low actionability and low mobility. This type of device will be an occasional distraction and often completely redundant.

Type II: Ambient technologies

(Complexity:L / Actionability:H)

Type II devices exhibit a powerful blend of having simple information along with being highly actionable. As noted above, the action to be taken may also be simple, however the user and designer are aligned in what that action should be.

When discovered, these types of devices become integral to the environment and to the users of them. Their success lies in that they are “missed” when they are no longer available to the user. This should be the holy grail for designers of ambient devices and user testing can rapidly determine whether a user feels lost when they have to give up a particular device after having it in their environment for a period of time to habituate to it.

Possibly one of the best examples of a Type II device is a clock - many people feel as though something is missing when they no longer wear a wristwatch or the clock on a wall is removed (or stops working). This is a fairly trivial example, but it's that type of feeling of utility and reliance the designer should be attempting to elicit when creating these types of devices.

Blink(1)

The blink(1) is a USB device that plugs into any computer and is essentially a scriptable USB powered RGB LED. In many ways, for a computer it is the same as the Android notification LED mentioned above and will fill the same role.

blink(1) by thingM

Again, high actionability comes because there will be a limited range of information conveyed but it will be highly actionable when it is because it was configured by the user which removes ambiguity from the display. One of my primary use cases is that I have large data processing pipelines that take some time to execute which occur in just one terminal window I may be using. Historically I just switch back every once in a while to see if it has completed. If I was being really fancy I could script an email notification but that's just cluttering my email with messages saying “Complete” a few times a day.

In this context the Blink(1) works well because it can be triggered when the job is complete and it will just change colour in my peripheral vision. If I'm at my computer I no longer need to keep checking, if I'm across the room I can see when it's done and go back if I need to.

This is low complexity, high actionability at work - I can immediately use the information to do something with it.

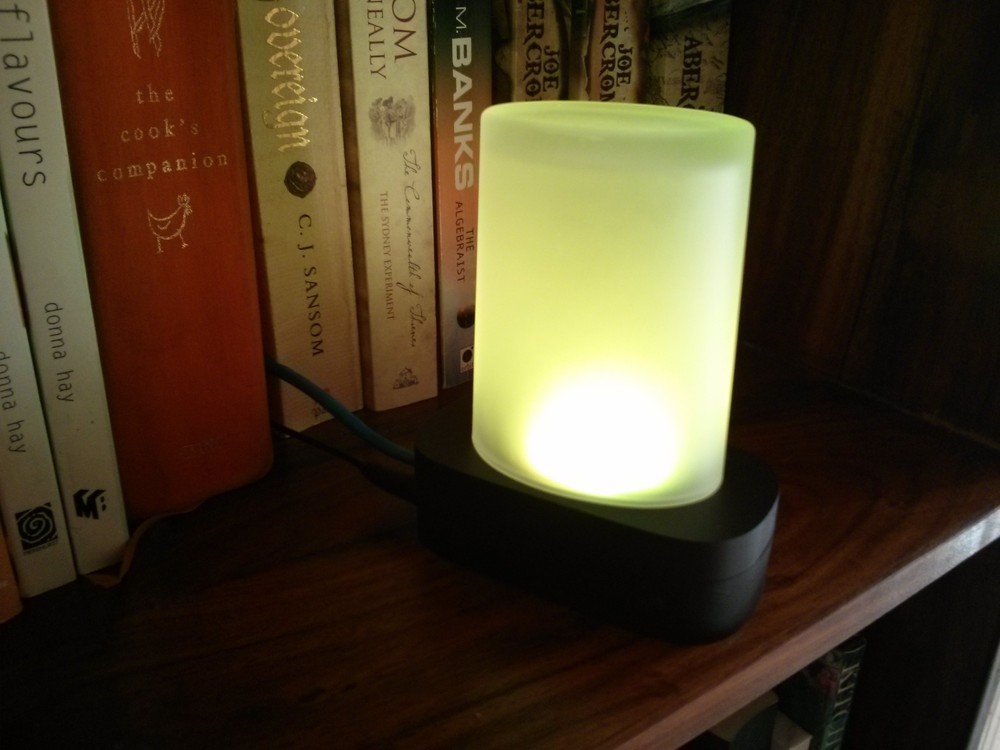

Ambient umbrella

Unfortunately no longer available (and they never worked in Australia), the Ambient Devices Umbrella was a great example of a Type II device. The umbrella had a radio chip and LED embedded into it which could highlight whether it was forecast to rain at your current location that day or not.

The use case was you left it somewhere you could see it (and keep it charged), such as an umbrella stand near your door, and without looking at the forecast you could glance at your umbrella to determine whether to take it with you that day or not.

This high actionability is the key to true ambient devices in our environment - they allow us to glance at the information they provide and take immediate action upon them as a result. The coupling to a device that is specialised lends additional actionability - looking at your umbrella as you leave the house is a natural thing one might do anyway and having a visual cue to prompt you to take it with you drives that actionability.

Type III: Ambient Art

(Complexity:H / Actionability:L)

Type III devices lend themselves towards interesting and beautiful pieces of data driven ambient art. Their actionability is typically low as there's no way to use the information provided to take action upon it directly. Instead, most art provokes some kind of response that may be more introspective or societal in action. For example a civic installation visualising crime locations and volumes may inspire action by residents to take action - at the least questioning what can be done to fix the problem.

Before us is the Salesman's House

This piece of generative art was commissioned as part of the Zero1 Biennele (http://www.zero1biennial.org/) in San Jose, USA and installed in the eBay campus there.

Before us is the Salesman's House - Three Cycles from blprnt on Vimeo.

Exploring the notion that databases will be the lasting cultural artefact of the 21st Century, the piece blends real time data from eBay with text extracted from a novel, each day starting with “Death of the Salesman”. Elements from within the selected text are looked up using the eBay data, visualising information about them historically before ultimately selecting a new book and extracting some text and starting the cycle again.

This type of ambient art is becoming more popular as a result of huge datasets becoming available to be coupled with projection or other display media.

Type IV: Command and control visualisations

(Complexity:H / Actionability:H)

At the extreme end of ambient technology are Type IV technologies, squarely aimed at Command and Control based applications. The best of these are typically envisioned in cinema (such as the battle display in the 80s film War Games), however they are becoming much more prevalent in business.

The key with Type IV displays is that they must be highly actionable otherwise there is the risk of information overload which, in some command and control scenarios, could even prove fatal as a critical piece of information goes unobserved or misunderstood.

In business contexts, the increasing use of tools such as Tableau (www.tableausoftware.com) and Splunk (www.splunk.com) to bring critical information to the eyes of decision makers (primarily through tablet use rather than tying a consumer to a desktop application) is streamlining decision making processes and speed at which decisions can be taken.

To be truly Command and Control, technologies need to be highly specific and are very contextual in nature. For example the C&C requirements of the traffic management system for a major city are extremely different to that of the commander of the rural bush fire services in Australia. A Network Operations Centre display is another interesting example, it provides glanceability (all systems are green) but it can also provide specificity to focus attention and action (why is that specific server orange?).

This highly contextual relevance drives many of the decisions about what to display and how to display it for maximal effectiveness.

Creating ambient technology as a function of context

As illustrated above, different contexts are afforded through the combination of mobility, actionability and complexity of information. Understanding the forces applied by context in this way allows a designer to consider the appropriate use of technology within this context rather than merely deploying a piece of technology and hoping that it works (which happens a lot in the ambient technology space).

A designer's role is to explore the spaces created at the intersection of constraints (contexts in this case) and technology and there are still many spaces to investigate given the emergence of this type of information design and art form. The examples given are by no means definitive, however they could be considered current canonical references for deploying ambient technology in the right way for a given context.

Understanding how new technologies can enhance or disrupt the way in which contexts drive the use of ambient technology means opportunities for new products, displays or artworks that previously didn't exist.

Avoiding the low actionability trap

The worst place to be in the model is at the intersection of low actionability and low complexity where you have created a distraction (Type I devices). As such, how do you design your way out of this problem?

Getting out means shifting one of the variables - either make the system highly actionable or more complex.

To increase actionability there are three ways to go about this. The first is to set the correct designer and user expectations around actionability. The second is to create a means to take action with the data and the third is to change the data represented to something more actionable.

You can also increase complexity in which case you want to consider how you transition the display to be more artistic in nature and think about the message you want people to take away (i.e. lean into the low actionability nature of what you're doing).

Finally, there are just some data points that are very difficult to action effectively - getting @'ed on twitter is a prime example. Few interfaces are more actionable than a twitter client on a mobile phone - which is probably more proximate than the piece of ambient display anyway. In this case, it may be more pertinent to think about other types of information that are also low complexity but require less action as a result of them, or actions that are more immediately viable given your interface restrictions.

Conclusion

As we rapidly proceed along the second function of Moore's Law (that a given level of computation gets cheaper over time) we are witnessing the transition to “computing as substrate”. Once achieved, this becomes the point where computation becomes a material that can be used heavily in the design process, as illustrated by Kuniavsky in “Smart Things”. Once computing as a substrate becomes commonplace, the amount of ambient technology we are exposed to will accelerate rapidly bringing with it a multitude of applications currently inconceivable.

This transitional period is a defining one, as many products and designs are not “consumer ready”. Rather than being despondent about this, a designer should look to the areas where most traction can be had, in ambient art, C&C systems as well as sketching with emergent technologies and ideas to explore the other spaces. In many cases failures will occur as a result of not correctly understanding the contributing factors to the context and how the end result is shaped by these. However the documentation of and learning from these failures is critical in the creation of more ambient technology and using it to enhance our spaces - whether in the form of information rich environments, art or simple informational knick knacks.

Acknowledgements

This was a long essay that took quite a lot of revision and input from others to make possible. In the end I sat on this for a very long time due to the amount of editing involved. To that end I would like to thank those who gave excellent and detailed feedback, Mike Kuniavsky, Jessica Smith and John Allsopp. If my writing is more clear it's because of their good work - any failings in that regard though are all mine.

Notes on the model approach

I've tried to express this nermous ways but this version survived the longest. Obviously, this approach is not expressed as a three dimensional model with three orthogonal axes - this is because I'm unsure they are truly orthogonal. I believe that mobility and actionability are facets of some higher function but am yet to work out what that is though they drive different behaviours on the end results. Possibly as we start to see more, higher level ambient devices in the wild, this will refine my thinking on the subject further.

Updates, corrections and modifications

This essay was originally written in the first part of 2013, but took a long time to pull together and went through many revisions. Due to work, life and the curse of editing such a big piece, this document wasn't published publicly until September 2023, a decade after it was started. Rather than let the content rot in a google drive folder, I decided to release it, but back date it to the time it was "mostly" done.

More significant revisions were made in September 2023 to clarify various items, update links to projects, and remove examples that have unfortunately disappeared from the Internet.