It’s been a long road, and one that has gone down some strange paths at times, but finally node-interchange has hit v1.

Node Interchange is a package and device manager for NodeBots related firmware, however it didn’t start out quite like that. This post discusses how the project got to this point and how the tension between hardware and software drives product development.

Interchange was a project that was born out of the Johnny-Five hack session that happened after Robots Conf ‘14. At this session (and prior to it) there had been a lot of discussion related to how we provide support for new components that were not directly supported by Firmata.

In the way of some background; Firmata is a firmware primarily designed for Arduino that exposes a MIDI-like protocol for control of the board. In essence, Firmata exposes an API to hardware so you can turn pins on and off, control servos, talk to I2C devices and read the states of sensors. It’s a great project, is very mature, and is also the most common way someone will experience NodeBots for the first time.

The challenge was that in the second half of 2014, Johnny Five had moved to IO Plugins. IO Plugins abstract the specifics of the board and the communications transport layer away from the Johnny Five application. With an IO plugin it became possible to easily run the same JS code against a Raspberry Pi, BeagleBone or Arduino just by changing the IO Plugin and a bit of wiring.

IO Plugins were expected to be able to implement certain low level operations such as turn pins on and off, read and write to I2C and other basic functions. As a result, any future extensions to the core of Firmata would create a requirement to extend the other IO Plugins. This wasn’t an ideal situation and one that created a considerable amount of design discussion.

The end point of this was to create a backpack - inspired by Adafruit and others who had used this approach previously - which is used to provide additional capability to an otherwise simple device. The idea was to build a low cost generic board which could have a firmware uploaded to it in order to control the component (eg a strip of NeoPixels). The backpack would then talk to the host board using I2C, a protocol that just about all of the boards Johnny Five runs on could support.

With that as the intent, going and actually building it started - a period that took close to a year to complete off and on.

Hardware backpack

The initial concept was to use the cheapest microcontroller possible in order to keep costs down. Part of the idea was that we would be in a position where we may be able to give away backpacks at events or in kits. The main chip under consideration was the ATTiny85 as it has USI (Universal Serial Interface) allowing for I2C communications and is pretty cheap (sub-$1 in even small volumes).

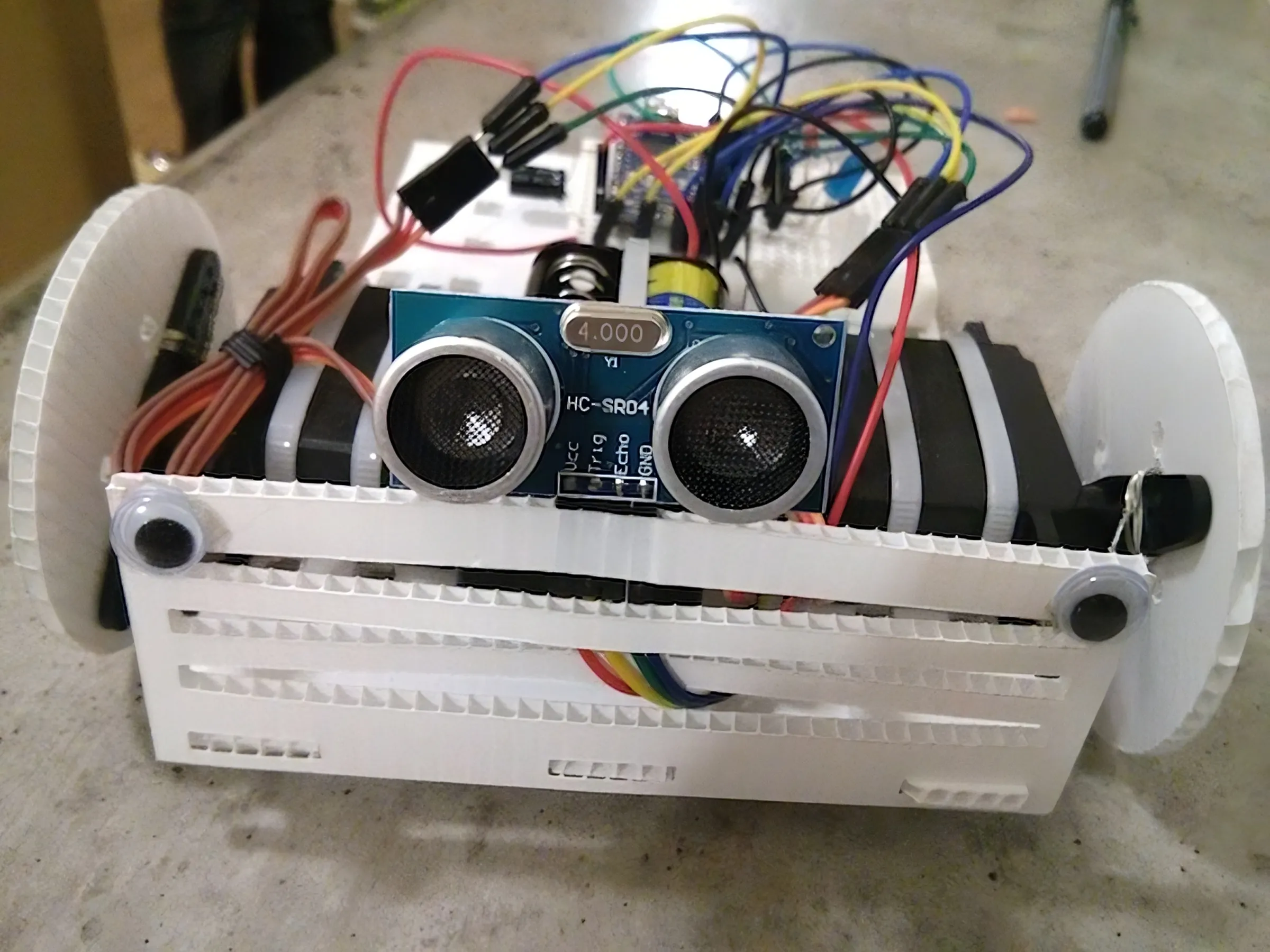

Given that the ubiquitous HCSR04 ping sensor was one of the main use cases for building backpacks in the first place, this component was the first prototype of the approach.

Spark Core Ultrasonic Project, image(cc) Gareth Halfacree

Spark Core Ultrasonic Project, image(cc) Gareth Halfacree

After some refinement with Jeff Hoeffs and Rick Waldron it became immediately apparent that whilst the idea of the backpack was solid, using it was a nightmare. Specifically:

- The build process sucked - a result of Arduino’s inability to properly deal with preprocessor directives (eg conditional includes) - meaning the end user had to manage included libraries and #defines in the code.

- Switching to avr-gcc helped resolve the technical issues but increased build complexity for the end user of the backpack.

- INOTool had fragmented and became an effectively non-maintained project (which could have simplified the acv-gcc interaction though it meant a python build chain).

These issues highlighted that many NodeBots end users weren’t close enough to the hardware build tools that we were familiar with through years of use and we couldn’t expect them to learn all of this just to get a ping sensor working or have some NeoPixels to light up. Something would have to be done to resolve this - we would have to have a documented build process for each firmware and automate the production of binaries and ship them so end users only needed to flash a hex file.

With that approach in mind, the process continued on the hardware, taking the other main use case - controlling NeoPixels and getting them to work with the backpack.

During this exploration, it became apparent that the ATTiny chip was far too underpowered in terms of capability (IO as well as available RAM). Coupled with no serial interface, it meant that as a developer it was a very time consuming process to create a backpack that would work reliably. Debugging was a huge frustration and relied on bit banging a serial interface which then took up more RAM and IO on an already limited chip.

At around this time, I was revising the SimpleBot project for NodeBots Day and switched to Arduino Nanos to get our project costs down and make them more accessible. A Nano could be had for less than $2 a unit at moderate volumes. Further, Arduino Micros (a nano without the USB interface) could be had closer to $1 per unit.

SimpleBot, image (cc) ajfisher

SimpleBot, image (cc) ajfisher

This started entering the price point that we were looking to achieve for the backpack with the benefit that we would have a full serial interface for debugging, a lot more RAM available and much more IO. As these boards are all ATMega328p based, it means a backpack can be simulated or adapted using any Arduino you had lying around.

The decision to go this path meant a much more positive developer experience and opened up a bunch of other software opportunities:

- The build process could be simplified to use the Arduino IDE

- Configuration could be done over USB Serial as could debugging

- More RAM and IO allows for more capability on the backpack

With that decided, it was time to focus on the software side of the backpack experience.

Developing for developers

One of the key things to come out of the initial prototyping phase was that the build and deploy process was a disaster for anyone who wasn’t familiar with the traditional hardware development cycle. Changing code, understanding preprocessor directives, installing libraries - these were all barriers to usability. My experience of working with developers at numerous NodeBots events reinforced the requirement that a backpack had to have low cognitive load. Learning a whole new software stack just for building was a waste of time when they were already having to learn hardware.

The implication of this was fairly obvious in retrospect - keep the developer within NodeJS and use tools she is already familliar with. This has the benefit of minimising the cognitive load required to simply get a backpack working as well as making it easier for future developers to contribute to the effort later.

The first step of this process was producing the hex file to be flashed to the board. Grunt was chosen for this job due to its developer familiarity in the JS world as well as being a mature piece of software.

Arduino has some quirks around how it builds a binary and specifically it has an inability to process sub folders to look for libraries. In the situation of both Node Pixel and the HCRS04 ultrasonic sensor, both a backpack and a custom firmata was required. Grunt was great as the two different core firmwares could be maintained independently but all the files could be organised by grunt during build. A secondary benefit of this approach meant that upstream libraries like Firmata could be included using git submodules allowing for even easier management of C libraries in a backpack codebase.

In a stroke of timing, the 1.6 release of Arduino introduced the Arduino Command Line interface. This still required the full build of the IDE however it meant that building bins could be scripted.

The pertinent parts of the gruntfile ends up looking like this to make it all work:

var arduino = process.env.ARDUINO_PATH;

var boards = {

"uno" :{

package: "arduino:avr:uno",

},

"nano": {

cpu: "atmega328",

package: "arduino:avr:nano:cpu=atmega328",

},

"pro-mini": {

cpu: "16MHzatmega328",

package: "arduino:avr:pro:cpu=16MHzatmega328",

},

};

module.exports = function(grunt) {

// dynamically create the compile targets for the boards in the list and

// save them out to a specific bin path for inclusion in the repo.

Object.keys(boards).forEach(function(key) {

grunt.config(["exec", "firmata_" + key], {

command:function() {

return arduino + " --verify --verbose-build --board " + boards[key].package +

" --pref build.path=firmware/bin/firmata/" + key + " firmware/build/hcsr04_firmata/hcsr04_firmata.ino";

},

});

grunt.config(["exec", "backpack_" + key], {

command:function() {

return arduino + " --verify --verbose-build --board " + boards[key].package +

" --pref build.path=firmware/bin/backpack/" + key + " firmware/build/hcsr04_backpack/hcsr04_backpack.ino";

},

});

});

};With the hex files built, the only major task left was to get them onto the board.

Enter AVR Girl

I’ll let Suz Hinton explain the motivations behind avr-girl but suffice to say the project is brilliant and the ability to flash boards using only JS meant complexity for interchange was simplified as a result.

With the work Suz had done on avrgirl, she became a great advisor for me during the latter parts of the Interchange development providing a valuable sounding board. At numerous points along the way, use cases were refined as a result of the joint work we were doing and it was great to see the NodeBots ecosystem evolve in front of our eyes.

After producing the first full end to end build and deploy to a piece of hardware, the realisation dawned that Interchange could be used beyond the context of backpacks and could streamline the problems with initial Firmata install as well (many beginning NodeBots developers stumbled at the point of the Arduino build process to get Firmata up and running). Further, in the case of custom firmatas such as that used by mBot or Node Pixel, they could be managed through the same interface as well.

Interchange as package manager

Suspending my other project commitments for a bit, I built towards what was expected to be the 1.0 release. Buzzconf was the next NodeBots workshop and I was determined that we would not be using arduino to flash firmware on the mBots used for that workshop.

It was weird having to work on multiple parts of a stack at the same time. One of the key features of Interchange is that you can query the board for things like what what firmware and version is on the board and do developer friendly things like be able to change the I2C address of a board without having to rebuild the entire firmware.

These decisions meant that Interchange had become a method of specifying your firmware as well as a means of packaging it up and an API for interacting with it from a management perspective too. Oh my!

During this period - with a lot of testing and debugging support from Suz Hinton, Derek Wheelden, Luis Montes and Anna Gerber - the core of Interchange got built. This included the ability to query and install both backpack and firmata firmwares from npm and github and support for numerous boards (thanks to avrgirl).

Suz provided more board support into avrgirl and Derek refined the command line interaction, including an interactive prompts to make the installation process even easier.

Interchange interactivity example.

Interchange interactivity example.

In the end, the deadline was met and the BuzzConf nodebots workshop went off without any significant hitches - related to installing firmware at least. It was immediately apparent how much faster the process was to get people up and running, especially in the case of a custom firmata like that needed for the mBot. Version 1.0 was officially published npm and started to be used.

Where next?

After such an intense period on the project and nearly a year in development, other than bug patches and questions, I’ve had to spend a bit of time away from Interchange, spending some time making things light up with Node-Pixel instead.

There’s renewed interest in backpacks now the tools and use cases for them are being established within the NodeBots community, so I expect more requirements will manifest themselves. There’s some syntactic sugar I want to implement with respect to all the ways you can install binaries and there’s a lot of work to be done on the firmware “database” - which is currently a JSON file in the Interchange repo.

Overall I’m happy about where the project is and where it will go next. I’m also really happy that I got to work with some great people on this project, in particular Suz and Derek and I’m hoping to do more work with them in the future.

If you want to check out more about Interchange here are some places to dive in further: